The Frictionless Future

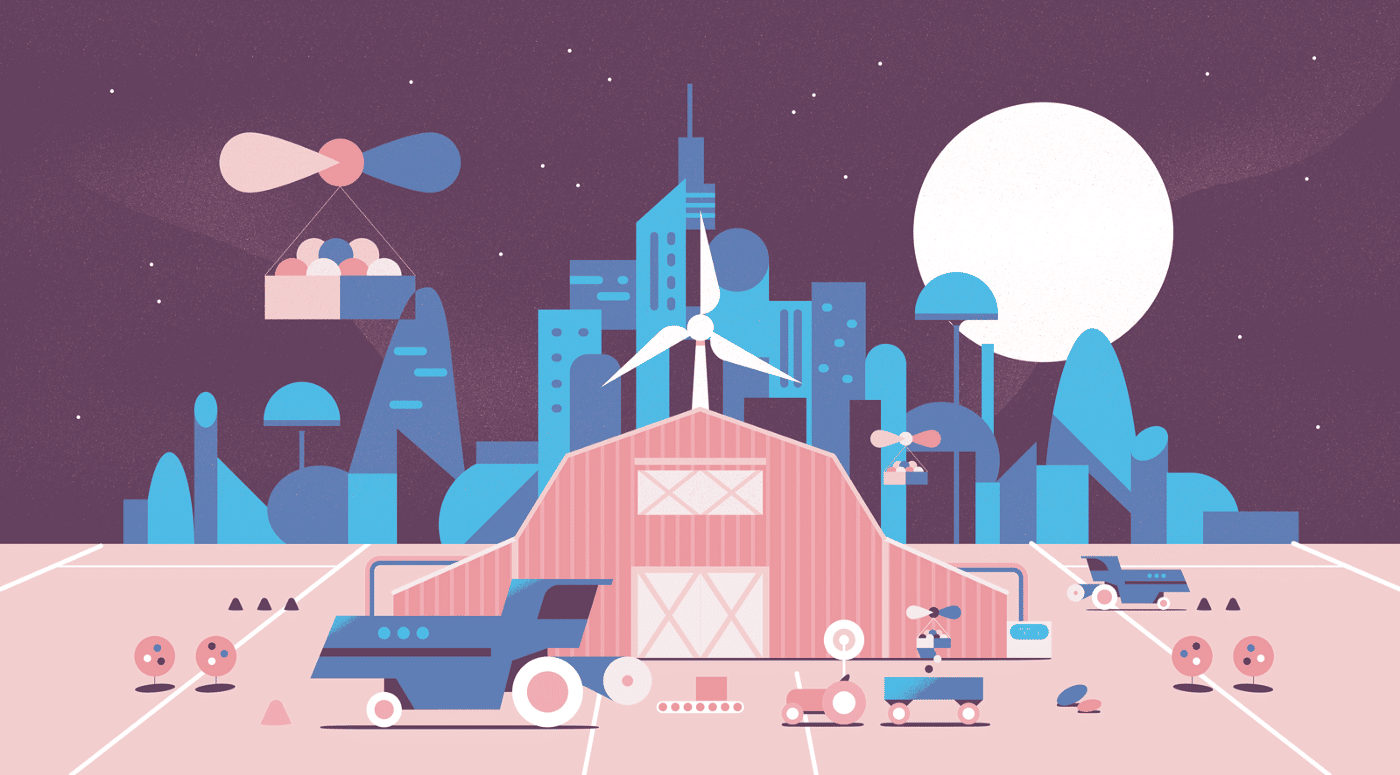

Urban infrastructure brings us closer to exponentially better living

Andrew Beebe |

An article I recently co-wrote with Di-Ann Eisnor sparked some controversy.

The post, about cities of the near future, took as a given that urban dwellers would represent an ever-larger share of the global population in the coming decades. Not everyone agreed. Why, one critic asked, do we take it as a self-evident that everyone wants to migrate to cities?

That question got me thinking more about what might be called the frictionless life, one defined by higher quality of living with deeper community connections. An unparalleled lack of friction, I believe, is a distinct advantage that the globe’s largest cities will enjoy in the near future.

What do I mean by the frictionless life?

It’s the efficiencies that come with fewer impediments between the products and services that we all seek, personally and professionally. It’s resilient energy generation and storage on-site, a hyper-efficient exchange of information, and more radically accessible products and services. It’s all of these, and much more.

Examples from today’s world include the electronic toll collection systems used on most bridges, public transportation tap-to-pay cards, the car that appears on a corner with one swipe on a phone, or the package that previously took a week to arrive but now shows up inside two hours.

Sometimes the frictionless life reveals itself when friction is reintroduced into a system. I had my own small reminder this spring when SFO designated new pickup spots for Uber and Lyft drivers. Their new system (i.e. passenger pickup atop the short-term parking garage) might have seemed like an efficient idea, but was far from it in execution: that night, a car that the app kept telling me was tantalizingly three minutes away took 25 minutes to arrive. It was as if this were another decade, and we were stuck in a long cab line at a congested airport. While far from tragic, it felt quite painful given the experience I’d grown accustomed to.

The frictionless life, of course, goes deeper than small annoyances. It is interwoven with everything we do—from what we eat to how we live—and is ultimately linked to the future of our livelihood and that of the planet.

Consider, for instance, energy production. Hyper-localized energy generation delivered more easily and efficiently—with less friction—translates into healthier air, lower emissions, and more resilient communities. Within the next decade or so, we’ll be demanding that the structures in which we live and work generate more (clean, naturally) energy than they consume. Translucent solar panels will become more routine in the construction of commercial properties and apartment buildings. Batteries placed throughout the building will ensure resiliency, lowering disruptions caused from centralized, fragile grids. We’ll also start expecting these buildings to capture, filter, and reuse water—implementing systems such as the one being developed by Swedish company Orbital Systems. The tech-enabled local food movement is another manifestation of this desire to reduce friction in our delivery systems: lower transportation costs, reduced fossil fuel usage as a result, and healthier food options (fresher produce = healthier) while strengthening local ecosystems.

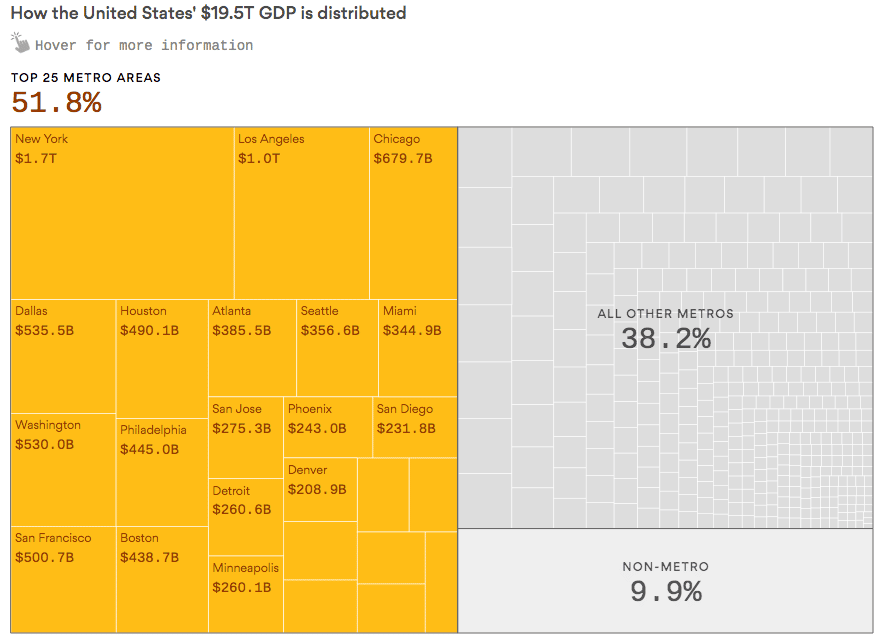

Critical mass and urban density explain why innovations that aim at reducing friction are far more likely to take place in large cities rather than smaller population centers. It’s easier to deliver 100 items in a 20-block radius than 10 items spread over 200 miles, just as it can be more efficient to offer a service to millions rather than tens or hundreds of thousands. Some benefits will spill over to areas outside the world’s largest urban centers. Breakthroughs and insights will no doubt come from geographies beyond the bounds of our urban centers. But economies of scale will mean cities continue to become increasingly attractive because they offer an ease of existence impossible to mimic elsewhere.

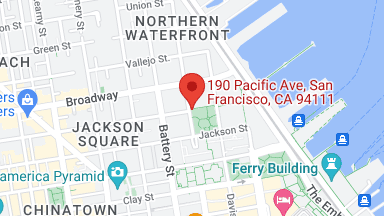

The key to this all is a new infrastructure that brings us closer to a more frictionless world. That’s of particular interest to us at Obvious Ventures, where we invest in brands facilitating a frictionless life and ultimately become essential elements of vibrant, urban ecosystems. In this world, people will have access to locally-produced food, goods, and services at faster speeds and lower costs. There will be greater transparency in the supply chain, deeper efficiencies in logistics and distribution, and massive leaps in local production. If we can seize the opportunity, cities will become more anti-fragile with cleaner skies and streets, more accessible goods and services, and ultimately happier, more connected people. The infrastructure now forming represents the building blocks on which these cities will be constructed over the next ten, twenty, and fifty years.

The Frictionless Life: Urban Nirvana?

One aspect of the frictionless life was captured by this short clip from a startup called Zippin, which pitches itself as the first AmazonGo rival to open an automated checkout store. In this short video, a professional woman stops by the market to pick up a few items. She checks in with her phone as she walks into the store and then tiny cameras do the rest. It’s in and out without so much as a pause at checkout. On the street, she glances at her phone: she has paid only for the two items she actually put in her bag and not others she picked up but back. That’s a frictionless world with a smile on the other end.

Zippin (and of course Amazon) promise to change the way we shop. So, too, does this idea of localized distribution through “dark stores”—warehouses that promise a wider selection and more efficient delivery. An example here is a Montreal-based company called Reno Run changing the way contractors access building materials, especially just in time. I’m impressed by their goal: provide contractors greater transparency into what they’re buying while simultaneously making it easier for them to do their job. They can also help with waste removal, making sure that recyclables are salvaged and properly repurposed—in sharp contrast with current standards.

Changes in the supply chain more generally are shaping up to be a big part of the infrastructure story. In time, supply chain transparency will soon broaden to include consumers wanting to know the toxicity of a device, say, or the assurance that a provider is certified and has been endorsed by others. Supply-chain transparency can help us clean up the food supply (e.g., no more mislabeled fish), show us which drywall is toxic, and more.

A shift in local distribution also promises to bring about sweeping changes and reduced friction for city-dwellers. Take a look at this clip and this one for a peek at the autonomous delivery systems FedEx and Amazon have been experimenting with. Imagine mobile robots rolling around our cities and/or drones swooping down from the sky to make deliveries of everything from medicine to meals. It’s already in process: Uber just announced that it will start experimenting with fast food delivery by drone in San Diego by the end of the summer.

Localized Production and 3D Miracles

Localized production is another building block as we move toward a more frictionless life. Consider 3D printers, which are getting less expensive and better each year. Carbon, the fastest-growing 3D printing startup, recently raised $260M at a $2.4 billion valuation with Sequoia’s Jim Goetz stating that they’ve “cracked the code on 3D printing at scale.” Makers, DIY’ers, and bleeding-edgers will have their own machines but I can imagine 3D printing centers around town, just like photocopying and overnight deliveries gave us Kinkos and FedEx. A missing screw or connector that can salvage an otherwise useful item—what if you could go to the corner and pick one up? 3D printers promise products made from resins, plastics, wood, metals, and even chocolate. Soda Stream, which stands as one of the great sustainability plays, is also an example of localized production, as is Bevi, a smart water dispenser that produces flavored waters (still or sparkling) on demand. Imagine if we didn’t have to ship a twelve-pack of bubbly anywhere, ever again. Guilt-free Alta Palla—now that’s low friction.

Another example of localized production: businesses bringing the farm to people’s homes. At the office, I’m growing chili peppers on my desk (courtesy of Click & Grow), opening up much wider possibilities of prosumer behavior. Memphis Meats in Berkeley is growing meat in vats using cells—and who knows what 3D printing might mean for food in the near future. We don’t seem far from a time when a new kind of communal living—the co-living buildings arranged by the likes of The Collective, for instance—also means kitchens where half the space is devoted to growing a portion of their food on their own. Vertical farms are growing lettuces and other leafy vegetables on the rings of our cities, which greatly reduces transportation costs, increases freshness, and delivers year-round access to healthier foods. In time, these same technologies will end up in the hands of consumers, who will use it to grow greens—and eventually more—at home.

One of our portfolio companies, Good Eggs, is a virtual store offering fresh, farm-grown food and all forms of locally-produced products delivered directly to urbanites. There are also “ghost kitchens,” which are shared-spaces where food entrepreneurs can make food for to-go and delivery customers. One player, Kitchen United (backed by GV), plans to be in 15 locations across the country by the end of the year, according to Bloomberg.

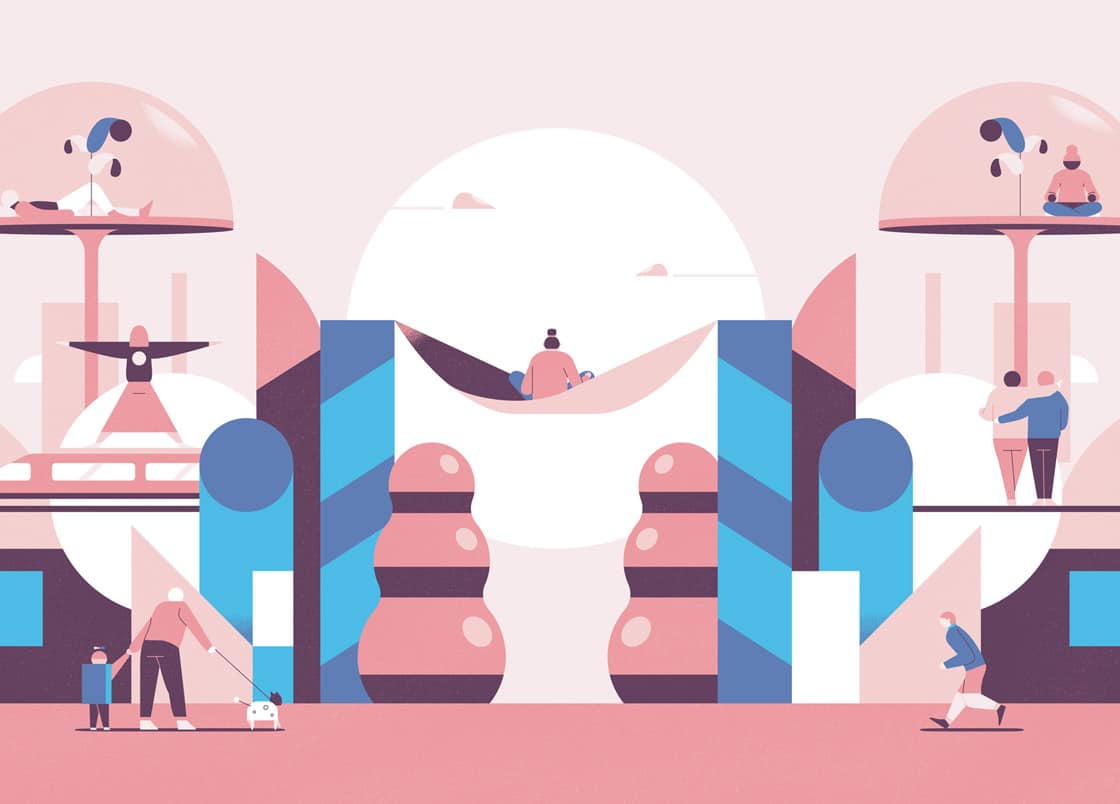

Urban Communities of the Near Future

If we’re not careful, some of what I’m talking about here can lead to a generation of shut-ins who push buttons in place of human interactions. The best remedy here might be the design of frictionless social engagements, starting with new communities taking advantage of these technologies. Again, it comes down to infrastructure—in this case, early efforts at building a different kind of community.

One noteworthy startup in this space is Roomrs. The company is embracing Millennial and Gen Z desires for a more fluid, flexible way of living, working, and traveling. Roomers offers co-living in townhouses and other properties where potential roommates find one another seamlessly, powered by their platform. Every resident is provided a personal code that gives them entry to their bedroom, a feature that is portable. Over time, roommates might grow food together, or connect at meal-time gatherings with food prepared by various delivery-only kitchens. This new generation will still crave community—and possibly find more of it than if they lived in a standard apartment building, where many people neither know nor socialize with those living right down the hall. Similarly, there’s Lyric, also in the Obvious portfolio, offering a shape-shifting way to look at community. Think Airbnb aimed at business travelers, enabling people to “discover a new way to live while you travel” in “creatives suites designed for the modern traveler.”

On that same business trip that ended in 25 minutes of Uber purgatory I ate a strip-mall dinner before parking myself at a sad bar to watch the Warriors lose a playoff game.

Imagine a frictionless version of that trip, one where my food is cooked by a budding chef-entrepreneur (made possible by a ghost kitchen), and a small group of us watch the game, drinking local beer delivered by Good Eggs in a Lyric suite. Less friction, more connection.